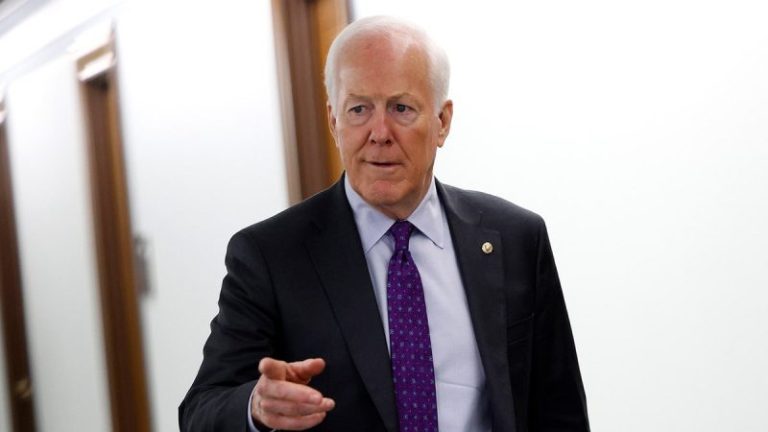

In a sharp break from his long-standing defense of the Senate filibuster, Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, urged Republicans Wednesday to enact ‘whatever changes’ necessary to send a Trump-backed voter ID bill to President Donald Trump’s desk before November’s midterm elections.

Cornyn, who is locked in a fierce runoff against Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, is pressing Senate Republicans to pass the SAVE (Safeguarding American Voter Eligibility) America Act — even if it means scrapping the chamber’s 60-vote legislative filibuster.

His appeal marks a significant reversal for the Texas Republican, who long argued the filibuster served as a safeguard against Democrats advancing sweeping left-wing priorities with a simple majority.

‘For many years, I believed that if the U.S. Senate scrapped the filibuster, Texas and our nation would stand to lose more than we would gain,’ Cornyn wrote in a New York Post op-ed Wednesday morning. ‘But when the reality on the ground changes, leaders must take stock and adapt.’

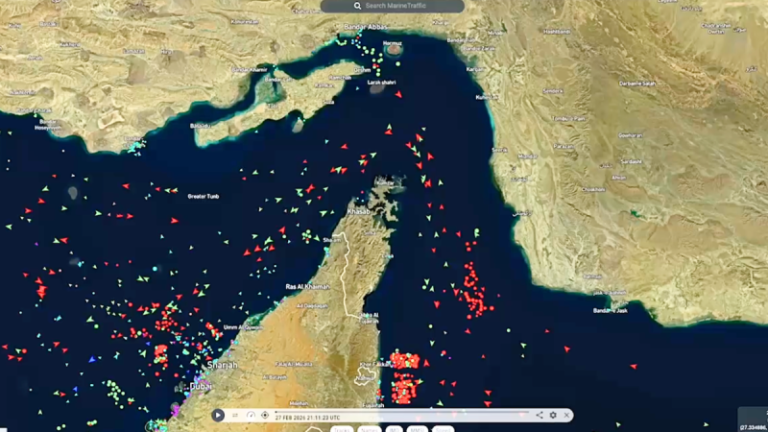

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., is expected to put the SAVE America Act to a vote in the Senate next week, but the measure could fail on the floor given widespread opposition from Democrats. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is also facing a weeks-long shutdown over Democrats’ refusal to fund the agency absent vast reforms to immigration enforcement.

Under Senate rules, both pieces of legislation would have to overcome the 60-vote threshold — meaning buy-in from some Democrats — to survive a key procedural vote before final passage.

‘Today, Democrats are weaponizing the Senate’s rules to block the SAVE America Act, defund the Department of Homeland Security and hurt the American people — all to spite President Donald Trump,’ Cornyn wrote.

‘After careful consideration, I support whatever changes to Senate rules that may prove necessary for us to get the SAVE America Act and Homeland Security funding past the Democrats’ obstruction, through the Senate and on the president’s desk for his signature,’ Cornyn added.

Trump has repeatedly called on the Senate to pass the voter ID bill, calling it the ‘number one priority’ during an address to House Republicans on Monday.

The House-passed legislation would require proof-of-citizenship to vote in federal elections, impose voter ID requirements and require states to remove noncitizens from voter rolls. Trump has asked Republicans to add provisions that crack down on mail-in ballots, prohibit biological males’ participation in women’s sports and ban child sex-change procedures.

Trump has also threatened not to sign any legislation into law until the SAVE America Act clears the Senate. The White House later clarified that DHS funding was not included in the president’s ultimatum.

‘We can either unilaterally disarm, or we can stand and fight,’ Cornyn wrote. ‘The answer is clear: We need to stand, fight and win.

Both Cornyn and Paxton are vying for Trump’s endorsement ahead of the late May runoff election that will decide who will face Democratic candidate James Talarico, a Texas state senator, in the November general election. Trump said last week that he would ‘soon’ back a candidate, but he has yet to issue an endorsement. Cornyn, who has served in the upper chamber since 2002, is seeking his fifth Senate term.

Paxton said last week that he would consider exiting the race if the Senate were to circumvent the filibuster and pass the SAVE America Act.

‘The SAVE America Act is the most important bill the U.S. Senate could ever pass, and I’m committed to helping President Trump get it done,’ Paxton wrote.

Despite Cornyn’s new openness to filibuster reform, the SAVE America Act still faces an uphill battle in the Senate. The bill passed the House last month in a vote mostly along party lines.

Thune, a supporter of the SAVE America Act, has repeatedly said that the votes do not exist to scrap the 60-vote filibuster and advance the voter ID measure.

The majority leader has also warned against using the talking filibuster — a little-used maneuver preferred by some conservatives — arguing that approach would have unintended consequences and risks jamming the Senate floor for an indefinite period.

‘The votes aren’t there for a talking filibuster,’ Thune said Tuesday.

‘I’m the person who has to deliver sometimes the not-so-good news that the math doesn’t add up, but those are the facts and there’s no getting around it,’ he continued.